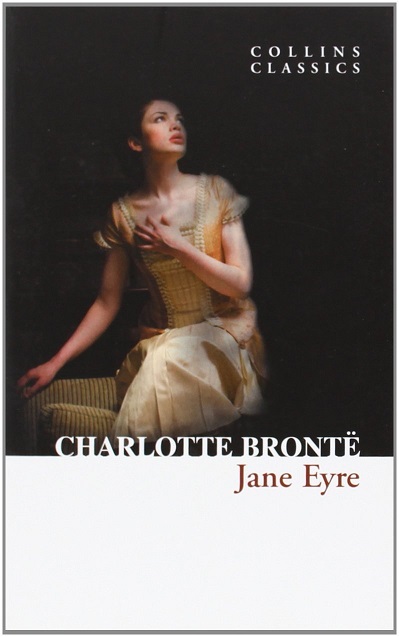

Jane Eyre, a novel by Charlotte Brontë published in 1874, is one of the most widely read literary masterpieces from the Victorian Era. In addition to being extremely well written, the story tells of a young orphan who is raised by a cruel aunt during childhood and goes on to become a governess at a manor named Thornfield. While teaching a French girl, Adèle, she is employed by Rochester, a dark mysterious man with whom Jane fell madly in love with.

During the Victorian Era, many women were expected to behave in a demure manner, and Brontë’s depiction of Jane as a free spirited, independent woman became a refreshing character that young female readers looked up to. Even Queen Victoria was a fan of the novel. She wrote, “[Jane Eyre] is really a wonderful book, very peculiar in parts, but so powerfully and admirably written, such a fine tone in it, such fine religious feeling, and such beautiful writings. The description of the mysterious maniac’s nightly appearances awfully thrilling. Mr Rochester’s character a very remarkable one, and Jane Eyre’s herself a beautiful one. The end is very touching - Jane Eyre returns to him and finds him blind, with one hand gone from injuries during the fire in his house, which was caused by his mad wife.”

Indeed, what makes Jane stands out as a modern woman is that she strongly refuses to be dependent on Rochester’s employment and salary. She sees herself as an equal to any man and questions Rochester’s character as human being even though she knows she is already in love. She says to Rochester, “Do you think I am an automaton? — a machine without feelings? and can bear to have my morsel of bread snatched from my lips, and my drop of living water dashed from my cup? Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! — I have as much soul as you — and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you. I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh: it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God's feet, equal — as we are!”

A woman not afraid to speak her mind and expresses her feelings, Jane is clearly not after Rochester’s status or wealth when she say “yes” to Rochester’s proposal. She acknowledges that she is not the most beautiful or wealthy woman in the world but her confidence always shines through. Despite sometimes having doubts about her own attributes and feeling unease when Rochester is flirting with other ladies such as Blanche Ingram, she is determined to trust her own instincts and chooses the path that is best for herself, not to let her heart over her head.

Later on in the novel, it became clear that Rochester has been locking his wife in the attic for quite sometime, and her name is Bertha Mason. Due to mental illness and an unhappy marriage, Rochester has been putting her on the third floor of the manor, and her presence has been haunting Jane on various occasions. For readers, Bertha is the complete opposite of Jane, as she is confined like an animal in a zoo. Jane, on the other hand, declares, “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me: I am a free human being with an independent will.”

Jane forgives Rochester but decides to run away from Thornfield. She finds herself a job teaching elsewhere and when another man proposed to her, she refuses to marry and one day returns to Thornfield and realises Bertha has died. Jane finally agrees to marry Rochester, who is now blind and handicapped. The happy ending sees Rochester’s sight restored and the couple having a son.

Throughout the novel there are several themes. Firstly, there is passion, characterised by the element fire and the madness of Bertha, it also encompasses feelings of having deep desires and secrets. Gender and class also constantly structure the behavioural patterns of the novel’s characters, but Jane does find a way to break through many notions of such. Her determination to guide her own independence and freedom is in truth very modern in the Victorian Era. Lastly, religion and self control echo throughout the plot and readers who pay attention to this theme will feel the tension that has been built up inside each characters’ role in society.

The name “Thornfield” is also an interesting pick as when one thinks of thorns, the idea of roses also arises from the subconscious, pointing to a world where bitterness and sweetness coexists and manifests themselves in numerous unexpected ways. Although we are now in the 21st century, Charlotte Brontë’s work is still relevant as its psychological realism invites us to also look at the state of our modern society.

Gender equality and social class struggle continues to be issues in many countries around the world and while we are busy fighting to neutralise differences, it is also essential to identify nuances in traditions, precisely target misunderstanding and respect diversity of viewpoints. Jane has shown us that no matter how difficult the circumstances are, when there is a will, there is a way to create a life she wants, but it is important to be determined and have confidence in oneself. Most of all, not being afraid of solitude is also a key. “I care for myself. The more solitary, the more friendless, the more unsustained I am, the more I will respect myself,” says Jane. “I can live alone, if self-respect, and circumstances require me so to do. I need not sell my soul to buy bliss. I have an inward treasure born with me, which can keep me alive if all extraneous delights should be withheld, or offered only at a price I cannot afford to give.”