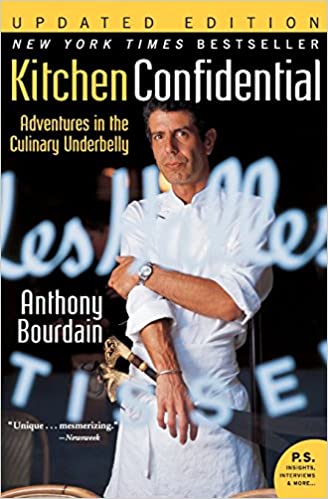

In the culinary world, everyone knows who Anthony Bourdain was. Most individuals started to notice his work from the day he became the host of the series No Reservations on the Travel Channel, yet many would agree that Bourdain’s most interesting writing was about the secrets behind the kitchen. Back in the days when he was the executive chef at Brasserie Les Halles in New York, he encountered numerous strange incidents and people and was not afraid to expose horror stories and disasters he had seen with his own eyes in Kitchen Confidential.

Why would someone open a restaurant? What does it take for one to cook like a professional? What kind of dishes sell well during the weekend? What kind of items should diners avoid for food safety reasons? These are some questions that Bourdain answered with thorough details, integrity and humour in his book. Writing as if he was speaking to industry outsiders, he would dissect the psychological aspects of those who were in the business and explain why emotional elements such as vanity, fear, and other human vulnerabilities would affect the outcome of people and places in the culinary world.

In a chapter titled “Owner’s Syndrome and Other Medical Anomalies,” Bourdain told the tale of a retired dentist in his fifties who was encouraged by his friends to open a restaurant because he threw great dinner parties as leisurely pursuits and therefore was made believe that he would be a good restauranteur. “He wants to get in the business - not to make money, not really, but to swan about the dining room signing dinner checks like Rick in Casablanca,” Bourdain explained.

The writer went on to point out that men having a midlife crisis are also prone to desires of opening up a restaurant. In the case of the retired dentist, deep in his heart he figured being a restaurant owner and the social possibilities the circumstance present might help him to appear more attractive to women who, otherwise, would not have found him to be alluring when he was “yanking molars and scraping plaque.”

The humour went on and Bourdain continued and described the “most dangerous species of owner,” those who get into the business for love of showing off their eighteenth-century French antiques or memorabilia from a Bogie film in their restaurant. Bourdain sympathized and was convinced that “these poor fools are the chum of the restaurant biz, ground up and eaten before most people even know they were around. Other operators feed on these creatures, lying in wait for them to fold so they can take over their leases, buy their equipment, hire away their help.”

The cruel and cut throat reality of the industry does not end with owning the business but also how food is served and prepared back in the kitchen, and having had worked in a competitive city like New York, Bourdain knew it all and was not afraid to dish the dirt. When one spends his or her hard-earned money to eat, it is only natural that the best ingredients are demanded. However, chefs must be sensitive about food costs and on days when the restaurant is not exactly packed and table turnover rate is less than satisfactory, issues arises.

“I never order fish on Monday, unless I’m eating at Le Bernardin - a four-star restaurant where I know they are buying their fish directly from the source. I know how old most seafood is on Monday - about four to five days old!” Bourdain warned in his chapter “From Our Kitchen to Your Table.

According to Bourdain, another way to decide if a restaurant is decent enough to be dine in is to check out the restroom. “I won’t eat in a restaurant with filthy bathrooms. This isn’t a hard call. They let you sell the bathrooms. If the restaurant can’t be bothered to replace the puck in the urinal or keep the toilets and floors clean, then just imagine what their refrigeration and work spaces look like,” he argued.

For any chef who is serious about his or her career, perseverance and a super hardcore work ethic might get one in the door but there are other nuances and unforeseen situations that push for improvisation and last minute wisdom. The line between failure and success is ultra thin. When Bourdain was working at Les Halles, he was always the first to arrive at his workplace. Before he hit the kitchen, he already had an idea of what to put on the special menu during the weekend.

“Saddle of wild hare stuffed with foie gras is not a good weekend special, for instance. Fish with names unrecognizable to the greater part of the general public won’t sell. The weekend is a time for buzzwords: items like shrimp, lobster, T-bone, crabmeat, tuna and swordfish. Fortunately, I’ve got some hamachi tuna coming in, always a crowd pleaser,” he said in the chapter, “A Day in the Life.

Although Bourdain is no longer with us, fans still cherish stories from his life and the commitment he had to show how human beings from different cultures have more similarities than differences. For him, moments of profound connection appeared out of nowhere when he was sharing a meal with someone who did not even speak English fluently. As an individual, his audacity to speak frankly and openly about concerns from horror stories in the kitchen to humanitarian crisis revealed the dedication he had to urge us to travel more and see the world in various perspectives that we might never had thought of.

In a world where chefs and food critics enjoy the glamour, prestige, and power in front of TV cameras, Bourdain’s remarks were often blunt and undiplomatic. His fame was a byproduct of his work rather than something he had worked hard for. While we lost this rare gem of a human being, let us celebrate his legacy and savour his words, for they might still bring us inspirations.