British nationals seeking refuge and protection through the British Consul in Macao will be disappointed to find their representative can only be contacted through a post office box number or by telephone, and that there is de facto no Embassy in the territory. They will be told: “There is no British Embassy in Macao. Macao is covered by the British Consulate- General in Hong Kong. We offer the same services to people resident in Macao as to people resident in Hong Kong. As we have no permanent office in Macao we can only offer these services remotely by phone or e-mail or by asking a Macao resident to attend our offices in Hong Kong personally”.

It was fortunate for not only British nationals, but others seeking refuge and protection, that this was not the case during the turmoil of the Second World War when the resident Consul, John Pownall Reeves, was instrumental in providing relief to 9,000 British subjects who had come as refugees mostly from Japanese-occupied Hong Kong. Reeves’ account of this traumatic period in the history of Macau territory, a sanctuary for those managing to escape the tyranny of Japanese conquest, is told in his wartime memoir dated 15 October 1949. However, its posthumous publication is due to the endeavours of editors Colin Day and Richard Garrett but ostensibly to Victor Millard who converted the text to a word-processed file. It was brought to Macao by Wilhelm Snyman, who was introduced to the editors by Professor Glenn Timmermans at the University of Macau. One might ask why there was such a delay in the publication of the memoir and be perhaps surprised to learn that Reeves was denied permission by the British Foreign Office to attest to the remarkable achievement of the British consul and his staff in the tiny enclave surrounded by Japanese-held territory.

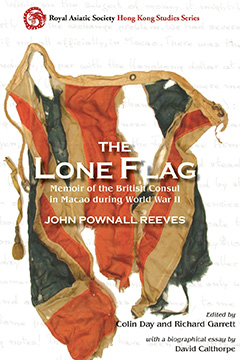

Perhaps the recalcitrant attitude of the Foreign Office is best summed up in Reeves own words about the perception of the role of a Consular Office: “In general Consular Officers only see British Subjects who are in trouble; when they are not they have no need to see a Consul: this state of affairs is enough to make Consular Officers feel that there is no British Subject but a British Subject in trouble.” The Lone Flag, documenting Reeves' role in Macau in the years 1941-1945, is a testament to the vicissitudes that were endured to help those not only in trouble, but marooned and desperate.

Reeves was eminently qualified to perform the role of Consul in Macao having spent two years in Beijing studying Chinese followed by appointments in Hankow and Mukden. He was somewhat bemused by the presence of a Consulate in the territory: “I have no knowledge of the origins of our own Consular representation in Macao. The Consulate-General at Canton was established in 1843 and was presumably in control and in charge of British Interests in Macao. At some point, I believe in the 1930s, Mr. F.J. Gellion, Managing Director of the Macao Electric Company, the senior British firm in Macao, became Honorary Vice-Consul, under the control of H.M. Consul- General at Canton. In 1940 the post became an independent Consulate in the charge of Mr. H.D. Bryan, a career officer, whom I replaced in June 1941 to, perhaps, Derek Bryan's later relief.” We may equally wonder why the Consulate ceased operations in the territory especially after it had served British nationals so well during the war.

During the Consulate's war years we are told that refugees from Hong Kong and neighbouring areas increased Macao's population to nearly 500,000 – an unprecedented influx that forced measures never undertaken before. The authorities had to cope with a Japanese sea-blockade forcing the territory to survive on its own food and supplies brought in from Guangdong Province; itself suffering from the ravages of war and occupation. Even though those able to prove they were British nationals received support from the UK Government in the form of an allowance, there was still the problem of procuring staples such as rice and bread. Refugees who were fortunate found succour with families or friends or places in homes, hospitals, schools, clubs and churches. Some however had to live on the streets and depend on charity for survival. The people of Macao were welcoming and provided what aid they could through institutions, lay and religious, Chinese and foreign, doing their best to feed the homeless with soup kitchens and distributions of bread, rice, clothing and blankets. With so many needy cases, Reeves appealed to the Foreign Office and arranged for telegraphic transfers of funds to meet the needs of those who were entitled to support.

Reeves explains the title of his memoirs‘The Lone Flag’which features on the cover of the publication: “It was to remain the only one constantly floating until the end of the war when it was described by the press as‘The Lone Flag’. It is possible that no other British flag has ever been so alone from the point of view of distance to the next.” The flag remained raised over the British Consulate in Macau until the Japanese surrender when soon after it was damaged by a typhoon that hit just as Reeves was preparing to leave the enclave. Ironically the Lone Flag flew in the company of another flag – that of the Rising Sun on the building next door which served as the Japanese Consulate: “My flag, floating next door to the Japanese Consul's, was the only Allied flag, apart from Chinese, for some distance, west to Yunnan and Chungking over 700 miles, north to Vladivostok 1,800, east into the Pacific some 4,000(?) miles, southeast to Port Moresby over 3,000 and south to Australia 2,700.” The proximity of the Japanese Consul, Mr. Fukui, was obviously fraught with dangers but Reeves describes him as“a fine man”and“The Governor [Gabriel Teixeira] once remarked of him that he ought to be promoted to another nationality.” Reeves would be indebted to Mr. Fukui for his intervention in securing the passage to Macao of his wife, Rhoda Reeves, who had been trapped in Hong Kong when the Japanese attacked. Mr. Fukui was also known to have facilitated the dispatch of food parcels to prisoners in Hongkong and personally brought letters from prisoners to their families in Macao. For these conciliatory gestures he was murdered by an assassin hired by the Japanese Gendarmerie.

The memoir chronicles the predicament of Macao as it struggled to maintain a semblance of normality despite the formidable task of catering to a burgeoning population. In twelve chapters we are given a picture of how the authorities and the population fared in terms of such issues as morale, organization of relief, and the provision of medical services. For the latter, the Government medical services were under severe constraints to cope with the problems: “What would have happened if a real cholera epidemic had broken out I hesitate to think; in those crowded streets half the population would have been swept away. It was owing to the vigilance of the Macao Medical authorities that this did not happen and they deserve great credit for this fact.” We are told drugs were in short supply particularly anti-epidemic vaccines and inoculations. Reeves was instrumental in setting up a Consulate Clinic although there was some conflict with local Portuguese doctors who did not benefit from the salaries paid through the Consul. Facilities were limited and equipment was “primitive”. Reeve however observes that their doctors and nurses were undaunted: “How well they succeeded was proved by the fact that the refugee death rate was less than that of London before the war and it must be remembered that the refugees neither arrived in a good condition nor had much opportunity of improving it.”

The chapter on‘Morale’is especially significant as it recounts how the refugees who arrived were acutely depressed; having lost their families or their homes and being faced with conditions that accentuated their desperation. For those who came relatively unscathed, one of the problems was how to pass the time when the need for food and shelter had been met. Centres were established to organize activities that would engage minds that were in danger of succumbing to feelings of futility. Hockey, a game at which Macao has traditionally excelled, was especially popular. Competitive football matches were organized although Reeve was on one occasion embarrassed to find himself“shaking hands with eleven members of the Japanese-employed Canton police all of whom were, at least in theory, my deadly enemies.”

The book contains twelve Appendices which pay tribute to the Consul and his staff in upholding the best traditions of British resilience and fortitude. We also gain some insight into the diplomacy of the Portuguese Governor, Comd. Gabriel Mauricio Teixeira who, on being invited to celebrate the Allied victory over the Japanese, “stated that from the beginning his heart was always with the Allies (Loud cheers), but his duty was to maintain the neutrality of the Colony at all costs.” To celebrate the cessation of hostilities, the Governor“lifted the ban on rejoicings and similarly that on firecrackers.” Reeve observed that“The noise of 400 thousand Chinese celebrating this way has to be heard to be believed; and we contributed a string [of firecrackers] or two ourselves.” Appendix 3, titled‘Mr. Reeves eulogised by Hongkong Portuguese Community’cites the words of José Pedro Lobo, with a personal tribute on behalf of the Portuguese community on presenting a token of gratitude: “Mr. Reeves: We know how inadequate is this demonstration of our respect and admiration for you. But I assure you that what I cannot interpret in words is deeply felt in each of our hearts; and I ask you to accept this souvenir, not for its intrinsic value, but as a token of sincere appreciation, esteem and gratitude of Hong Kong Portuguese refugees in Macau.”

The original of the memoir is in the possession of David Calthorpe, who, as a child knew John Reeves and heard his stories first-hand. Colin Day, the editor explains that“Both by inheritance and diligent efforts of recovery, David holds much of the memorabilia of John Reeves.” It is fitting therefore that the final chapter of the book has been written by David Calthorpe and we are told of Reeves’endearment to Macao: “Macao always had a special place in John's heart. He would talk about it in a tone of a lover reminiscing over faded memories.” It is perhaps hard to imagine how this affection could have been sustained given the circumstances of his brief but traumatic sojourn in the territory. However, Calthorpe attests: “Macao was central to John's life and, indeed, the crowning point of a career that was curtailed by circumstances, both personal and otherwise.” Although this book is a testament to the fulfillment of his duty, Calthorpe argues, “His work speaks for itself in the memoir, yet to him it was more than just duty to king and country. It was a deep love for China, and in particular, the city of Macao and its people.” Reeve left for a new appointment in Rome in 1946 and in the same year was awarded the Order of the British Empire in his capacity as consul in Macao.

The Lone Flag conjures up a final image that commemorates the peaceful transition of Macao and Hong Kong from the dark days of the Second World War up to China's recovery of its territories. We may be reminded of the ceremonious folding of the lone Portuguese and British flags and their final relinquishment during the Handover. Of course the Portuguese flag still flies over the Portuguese consulate and the consul's residence in the former Bela Vista Hotel. It is undoubtedly with pride that the flags of the Macao and Hong Kong Special Administrative regions now fly, not alone, but alongside that of the People's Republic of China.